Jobs Growth Slows in November Struck By Second Wave

Canada's Jobs Recovery Slowed Again in November With Second Wave

Hospitals and schools drive growth in public sector employment

The number of public sector employees grew by 32,000 (+0.8%) in November and exceeded its pre-COVID February level by 1.5%. On a year-over-year basis, the number of public sector workers was up 61,000 (+1.6%), driven mostly by increases in hospitals and elementary and secondary schools (not seasonally adjusted).

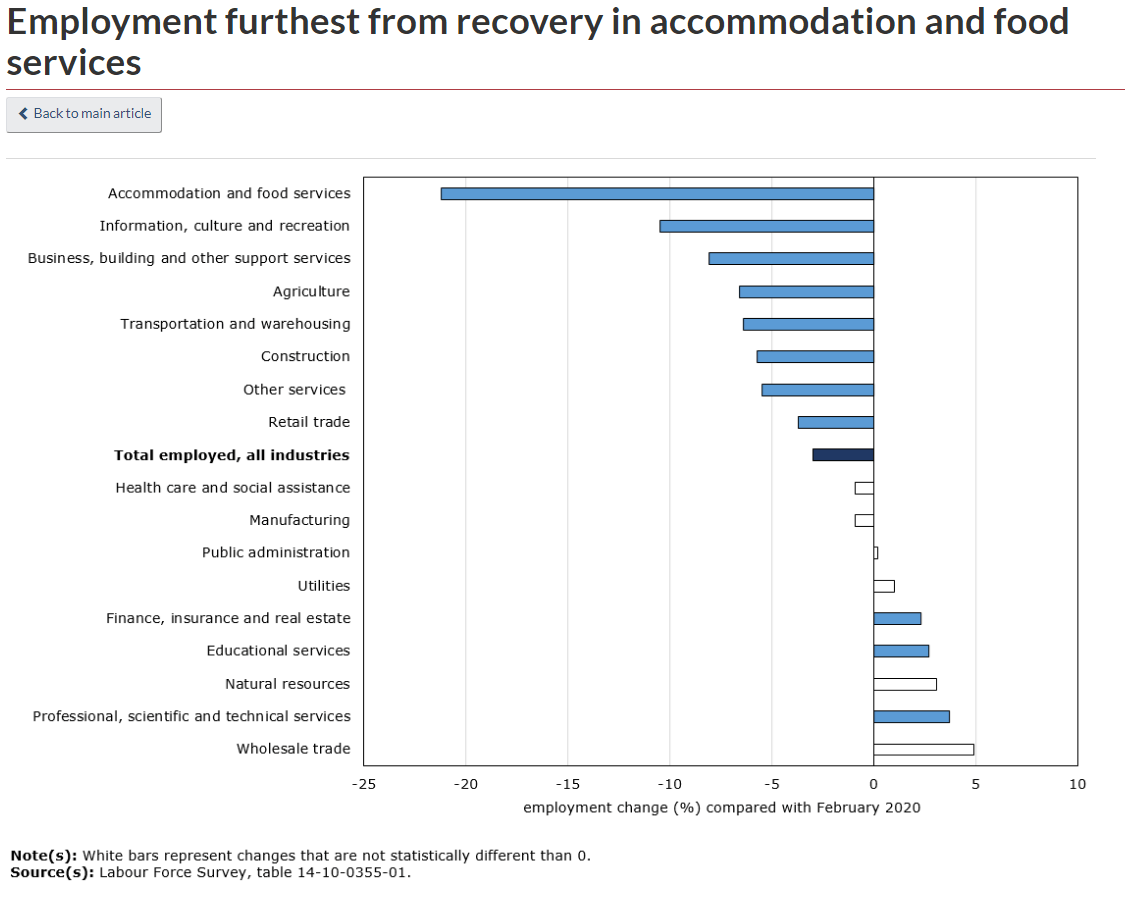

The number of private-sector employees was little changed in November but was down by 411,000 (-3.3%) compared with 12 months earlier. This decline was largest in accommodation and food services, while employment in professional, scientific and technical services increased (see chart below).

Growth in self-employment stalled in November, and this group remained furthest from November 2019 (-4.5%; -131,000) and from the February pre-COVID level (-4.7%; -136,000).

Employment declines in leisure activities & accommodation and food services

In November, employment in information, culture and recreation declined by 26,000 (-3.5%), the first notable decline for this industry since April. Employment fell for a second consecutive month in Quebec, where restrictions on public gatherings had been notably tightened as of the Labour Force Survey reference week. At the national level, employment in information, culture and recreation was 10.5% lower in November than in February (see chart below).

Employment in accommodation and food services declined for the second consecutive month, falling by 24,000 (-2.4%) in November, with the drop being shared between Ontario, Manitoba and Quebec. Nearly 1 in 10 (8.9%) employees in accommodation and food services worked less than half their usual hours in November—the third-highest share among all industries, following business, building and other support services (10.3%), and transportation and warehousing (9.2%) (not seasonally adjusted).

Statistics Canada conducted the Canadian Survey on Business Conditions to collect information on businesses' expectations moving forward from mid-September to late October. Almost one-quarter of businesses in accommodation and food services (22.5%) expected to reduce their number of employees over the next three months, more than double the average across all businesses (10.4%).

Second consecutive employment increase in retail trade

In retail trade, employment grew for the second consecutive month, rising 1.5% in November (+32,000), with most of the month-over-month increase in Ontario. Shutdowns of in-person shopping at non-essential retailers were introduced in Toronto and Peel on November 23, after the LFS reference week. They may be reflected in the December LFS results. December results may also shed light on the effect of tighter restrictions in other provinces such as Manitoba and Alberta.

At the national level, the employment increase in November brought retail trade within 3.7% of its pre-COVID employment level.

Employment growth resumes for construction and transportation and warehousing

Employment in construction rose by 26,000 (+1.9%) in November, the first increase since July, largely due to a 5.5% (+28,000) increase in Ontario. Nationally, employment in construction was 5.7% below its February level.

After pausing in October, employment growth resumed in transportation and warehousing in November (+20,000; +2.1%). The increase was largely the result of gains in Ontario and British Columbia, bringing employment in this industry to within 6.4% of its pre-COVID level.

Finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing now exceeding pre-COVID employment levels

Employment rose for the third consecutive month in finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing, up by 15,000 (+1.2%). The recent employment growth in this industry pushed it fully into recovery territory, surpassing its February level by 2.3%.

Employment up in natural resources for the second consecutive month

In natural resources, employment rose for the second consecutive month, rising 3.1% in November (+10,000) and returning to its pre-COVID level. The month-over-month gain was nearly equally split between Alberta and British Columbia. Data for this industry over the next few months may shed light on Alberta's impact, ending its limits on oil production in December, allowing producers to utilize available pipeline capacity and increase employment.

Labour market conditions vary across provincesEmployment increased in six provinces: Ontario, British Columbia and in all four Atlantic provinces. Manitoba experienced its first employment loss since April, while the number of people with a job or business held steady in Quebec, Saskatchewan and Alberta.

By November, employment levels in Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick had returned to pre-COVID levels. Employment was nearest February levels in British Columbia (-1.5%) in November and farthest in Manitoba (-4.8%) and Alberta (-4.9%).

Employment growth continues to slow in Central Canada

Following average monthly employment growth of 3.1% from June to September, Ontario saw slow growth in October. This continued in November, as employment rose by 37,000 (+0.5%), mostly in full-time work. Employment in the Toronto CMA was at a standstill in November after increasing for five consecutive months. The Ontario unemployment rate fell 0.5 percentage points to 9.1%.

The largest employment gain was in construction, an industry not affected by recent restrictions. Simultaneously, there were declines in accommodation and food services amid the tightening of public health measures in the City of Toronto and the Region of Peel.

Employment in Quebec was little changed for the second consecutive month. In the Montréal CMA, employment was flat for the second consecutive month following average monthly growth of 3.8% from May to September. The Quebec unemployment rate fell 0.5 percentage points to 7.2% as fewer people were on temporary layoff.

Employment fell in accommodation and food services and information, culture and recreation, coinciding with the targeted public health measures since October. Employment increased in professional, scientific and technical services.

Continued employment growth in British Columbia

Just before the start of the LFS reference week of November 8 to 14, the Vancouver Coastal Health Region and the Fraser Health Region introduced new restrictions on social gatherings, travel, gyms, and indoor sports facilities as new COVID-related workplace safety requirements.

Despite these new restrictions, employment in British Columbia grew by 24,000 (+1.0%) in November, adding to the gains over the previous six months (+335,000). Losses in part-time employment partly offset gains in full-time work. Several industries saw increases, including accommodation and food services, transportation and warehousing, wholesale and retail trade, and construction. The unemployment rate fell 0.9 percentage points to 7.1%.

Employment grew (+1.2%) in the Vancouver CMA, albeit slower than in the previous two months.

More people working in Atlantic Canada

Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick all had employment gains in November.

Nova Scotia posted the largest employment increase among the Atlantic provinces, up 10,000 (+2.2%), continuing the upward trend since April. The increase in November was mostly in full-time work. The unemployment rate fell 2.3 percentage points to 6.4%, the lowest since March 2019 and the lowest among the provinces.

New Brunswick posted its first significant employment gain (+4,200; +1.2%) since the substantial increases in May and June. The increase in November was nearly all in full-time work, and the unemployment rate fell 0.5 percentage points to 9.6%.

Employment in Newfoundland and Labrador rose for the seventh consecutive month, up 2,300 (+1.0%) in November, and regained all of the losses sustained since February. The unemployment rate in November was little changed at 12.2%. Industries with employment losses at the start of the pandemic, such as natural resources, construction and manufacturing, saw small increases in subsequent months and offset the declines in March and April. Others, such as healthcare and social assistance and public administration, continued to gain employment in recent months, pushing their employment above February levels.

Prince Edward Island also had more people working in November (+1,000; +1.3%), and the unemployment rate was 10.2%.

Employment losses in Manitoba

Employment in Manitoba decreased by 18,000 in November, nearly all in part-time work. This was the first notable decline since April and coincided with tighter public health measures introduced in early November for the Winnipeg metropolitan region and the rest of the province by the LFS reference week. The largest employment decrease was in accommodation and food services. The unemployment rate was little changed in November at 7.4% as fewer Manitobans participated in the labour market.

In both Saskatchewan and Alberta, there was little employment change in November. As of the LFS reference week of November 8 to November 14, both provinces had largely avoided introducing tighter public health measures. The unemployment rate in Saskatchewan increased 0.5 percentage points to 6.9%, with more people looking for work, while the Alberta unemployment rate was little changed at 11.1%.

Bottom Line

The economic recovery remains dependent on the evolution of the pandemic. The best news we've had in the past month is the successful development of efficacious vaccines. The timing of approvals and distribution is uncertain, but it is safe to say that the worst of the pandemic will continue this winter, with a seasonal reprieve in the spring and summer. By then, the distribution of the vaccine will hopefully be well underway. That means that 2021 will be a transition year, and in 2022 we can expect the economy can move from recovery to expansion.

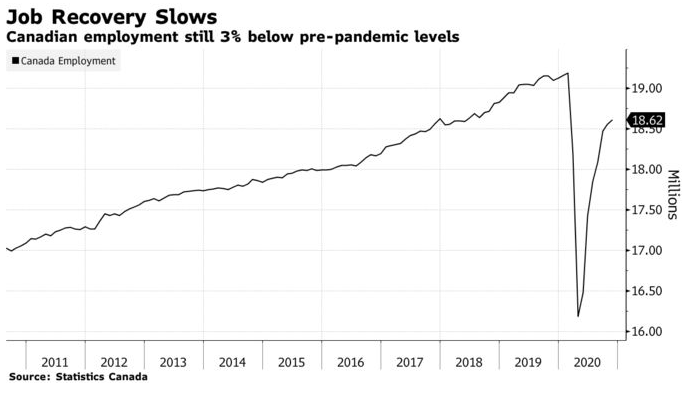

There was good news in this Labour Force Report. Although job gains slowed, total hours worked rose by an impressive 1.2% m/m. Following a decent 0.8% rise in the prior month, this big gain "builds in" a strong 14% annualized gain for all Q4 for hours worked. Note that total hours are one of Ottawa's three new "guardrails" for judging when to rein in fiscal stimulus; both of the other two also improved, with unemployment falling 81,000 and the employment rate nudging up 0.1 tick to 59.5% (it's still 2.3 ppt below pre-Covid levels). Average hourly wages eased again, as expected, but remain robust at 5.0% y/y.

We suspect the job cuts in the hospitality sector, and possibly retail, will bite much deeper in next month's report, as restrictions tightened notably immediately after this survey period. Overall, the report is firmer than expected and suggests that the economy is dealing a bit better than anticipated with the early stages of the second wave.

This article was written by DLC's Chief Economist Dr Sherry Cooper and was syndicated with permission.